Influenza B, a significant contributor to seasonal flu outbreaks, affects millions annually, causing substantial health and economic impacts. Unlike Influenza A, which can infect multiple species and cause pandemics, Influenza B primarily affects humans, leading to milder but still serious respiratory illnesses. This article provides an in-depth exploration of Influenza B, focusing on its symptoms, treatment options, and comprehensive prevention strategies to help individuals and communities stay protected.

Understanding Influenza B

Influenza B is one of two main types of influenza viruses (alongside Influenza A) responsible for seasonal flu epidemics. It belongs to the Orthomyxoviridae family and is divided into two lineages: B/Yamagata and B/Victoria. These lineages circulate globally, with one often dominating a given flu season. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Influenza B accounts for approximately 20-30% of flu cases in the United States each year, with children being particularly vulnerable due to their developing immune systems.Unlike Influenza A, which can undergo antigenic shift (major genetic changes leading to pandemics), Influenza B undergoes antigenic drift, resulting in gradual mutations. This makes it less likely to cause pandemics but still capable of causing significant illness, particularly in high-risk groups such as children, the elderly, and those with chronic conditions. Understanding its characteristics is crucial for effective management and prevention.

Symptoms of Influenza B

Influenza B symptoms typically appear suddenly, within one to four days of exposure. Common symptoms include:

Fever and Chills: A high fever (100°F to 104°F) is often the first sign, accompanied by chills and sweats.

Respiratory Issues: A dry cough, sore throat, and nasal congestion or runny nose are prevalent.

Body Aches: Severe muscle and joint pain can make movement uncomfortable.

Fatigue: Extreme tiredness may persist for days or weeks.

Headache: Intense headaches are common, often exacerbated by fever.

Gastrointestinal Symptoms: In children, Influenza B may cause nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea, though these are less common in adults.

Symptoms typically last 5-7 days, but fatigue and cough may persist longer. In severe cases, Influenza B can lead to complications such as pneumonia, bronchitis, sinus infections, or worsening of chronic conditions like asthma or heart disease. High-risk groups, including pregnant women, individuals over 65, and those with compromised immune systems, face a higher risk of hospitalization or even death. The CDC estimates that flu-related hospitalizations in the U.S. range from 140,000 to 710,000 annually, with Influenza B contributing significantly.

Diagnosis and Testing

Diagnosing Influenza B relies on clinical evaluation and, when necessary, laboratory testing. Healthcare providers assess symptoms and medical history, but confirmation often requires rapid influenza diagnostic tests (RIDTs), which detect viral antigens in nasal or throat swabs. These tests, available at clinics, provide results in 10-15 minutes but may have false negatives, especially if performed late in the illness. Molecular tests, like RT-PCR, offer higher accuracy but are more expensive and typically used in hospitals or public health labs. Early diagnosis, ideally within 48 hours of symptom onset, is critical for effective treatment.

Treatment Options for Influenza B

While many cases of Influenza B resolve without intervention, treatment focuses on relieving symptoms, preventing complications, and shortening illness duration. Key approaches include:

1- Antiviral Medications: Antiviral drugs are most effective when started within 48 hours of symptom onset. Common options include

Oseltamivir (Tamiflu): Taken orally, it reduces symptom duration by 1-2 days and lowers complication risks. It’s approved for all ages.

Zanamivir (Relenza): Inhaled, it’s suitable for those over 7 but not recommended for people with respiratory conditions like asthma.

Baloxavir Marboxil (Xofluza): A single-dose oral drug for those over 12, it inhibits viral replication and is effective against Influenza B.

Peramivir (Rapivab): Administered intravenously, it’s used for severe cases or hospitalized patients.

Antivirals are particularly recommended for high-risk groups to prevent severe outcomes. However, they may cause side effects like nausea or headaches, and overuse can contribute to antiviral resistance, a growing concern noted in recent CDC reports.

2- Supportive Care: Most patients rely on supportive care to manage symptoms:

Rest: Adequate rest boosts immune recovery.

Hydration: Drinking water, broths, or electrolyte drinks prevents dehydration, especially if fever or vomiting occurs.

Over-the-Counter Medications: Acetaminophen or ibuprofen can reduce fever and body aches, while decongestants or cough suppressants alleviate respiratory symptoms. Avoid aspirin in children due to the risk of Reye’s syndrome.

Humidifiers: These ease congestion and soothe sore throats.

Severe cases may require hospitalization, oxygen therapy, or mechanical ventilation for complications like pneumonia. Early medical attention is critical for high-risk individuals showing signs of respiratory distress or persistent high fever.

Comprehensive Prevention Strategies

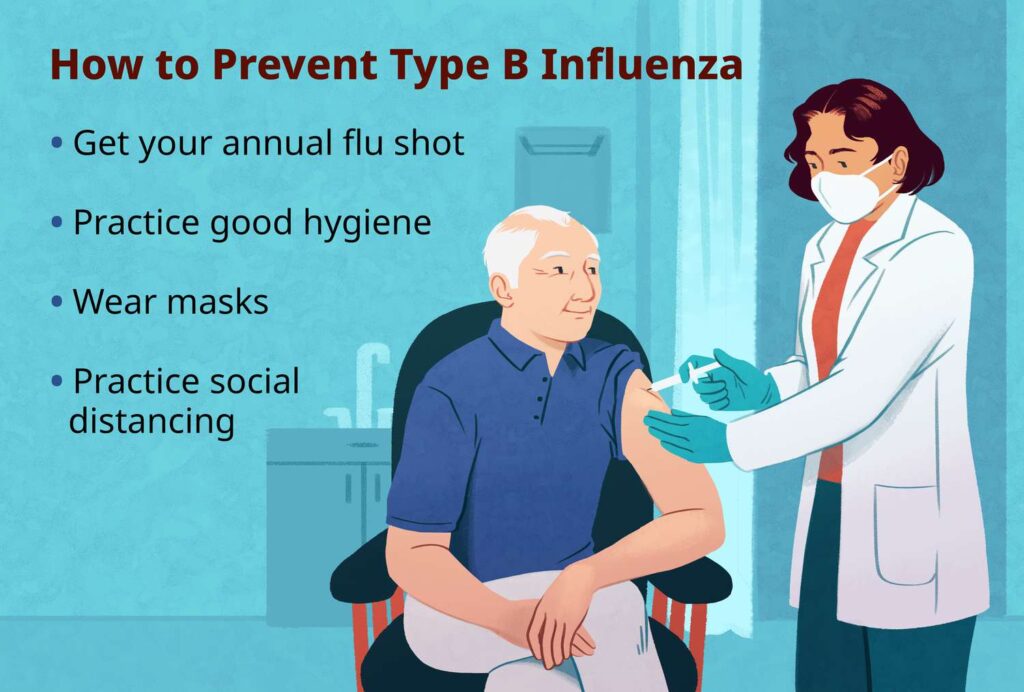

Preventing Influenza B requires a multifaceted approach, combining vaccination, hygiene practices, and public health measures. Below are key strategies:

1. Annual Vaccination: The flu vaccine is the most effective way to prevent Influenza B. Updated annually to target circulating strains, including B/Yamagata and B/Victoria, the vaccine reduces infection risk by 40-60% when well-matched to circulating viruses, per CDC data. Vaccines are available as injections or nasal sprays and are recommended for everyone over 6 months, particularly high-risk groups. Side effects are mild, such as soreness or low-grade fever, and severe allergic reactions are rare (less than 1 in 100,000). Vaccination also reduces illness severity and hospitalization rates, even if infection occurs.

2. Hygiene and Lifestyle Practices: Good hygiene significantly lowers transmission risk:

Handwashing: Wash hands with soap for at least 20 seconds, especially after touching surfaces or coughing.

Cover Coughs and Sneezes: Use a tissue or elbow to prevent spreading respiratory droplets.

Avoid Touching Face: This reduces virus entry through the eyes, nose, or mouth.

Healthy Habits: A balanced diet, regular exercise, and adequate sleep strengthen immunity.

3- Environmental Controls

Ventilation: Ensure well-ventilated spaces to reduce viral concentration in the air.

Surface Cleaning: Disinfect high-touch surfaces like doorknobs and phones regularly.

Masks: Wear masks in crowded or high-risk settings, especially during flu season (typically fall to spring).

4- Public Health Measures: Community-level efforts are vital:

Stay Home When Sick: Isolate for at least 24 hours after fever subsides to prevent spreading the virus.

School and Workplace Policies: Encourage sick leave and remote work during outbreaks.

Public Awareness Campaigns: Educate communities about flu risks and prevention, as seen in CDC’s annual flu campaigns.

5- Antiviral Prophylaxis: In high-risk settings, such as nursing homes, antivirals like oseltamivir may be used preventively after exposure to Influenza B. This is typically reserved for unvaccinated individuals or during outbreaks.

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite advances, Influenza B remains a public health challenge. Vaccine effectiveness varies yearly due to antigenic drift, and vaccine hesitancy, fueled by misinformation, reduces coverage. The CDC reports that only about 50% of U.S. adults get vaccinated annually. Antiviral resistance is another concern, with some Influenza B strains showing reduced susceptibility to oseltamivir. Additionally, global surveillance systems must improve to predict circulating strains accurately.Looking ahead, research into universal flu vaccines, targeting conserved viral components, could revolutionize prevention, eliminating the need for annual updates. Advances in antiviral therapies, such as novel drugs targeting multiple viral pathways, are also promising. Public health efforts must focus on increasing vaccine uptake, combating misinformation, and improving access in underserved communities.

Conclusion

Influenza B, while less notorious than Influenza A, poses a significant health threat, particularly to vulnerable populations. Recognizing its symptoms fever, cough, body aches, and fatigue—enables early diagnosis and treatment with antivirals or supportive care. Comprehensive prevention, centered on vaccination, hygiene, and public health measures, is key to reducing its impact. By staying informed and proactive, individuals and communities can mitigate the burden of Influenza B, paving the way for healthier flu seasons. As research advances, the future holds promise for more effective tools to combat this persistent virus, ensuring better protection for all.